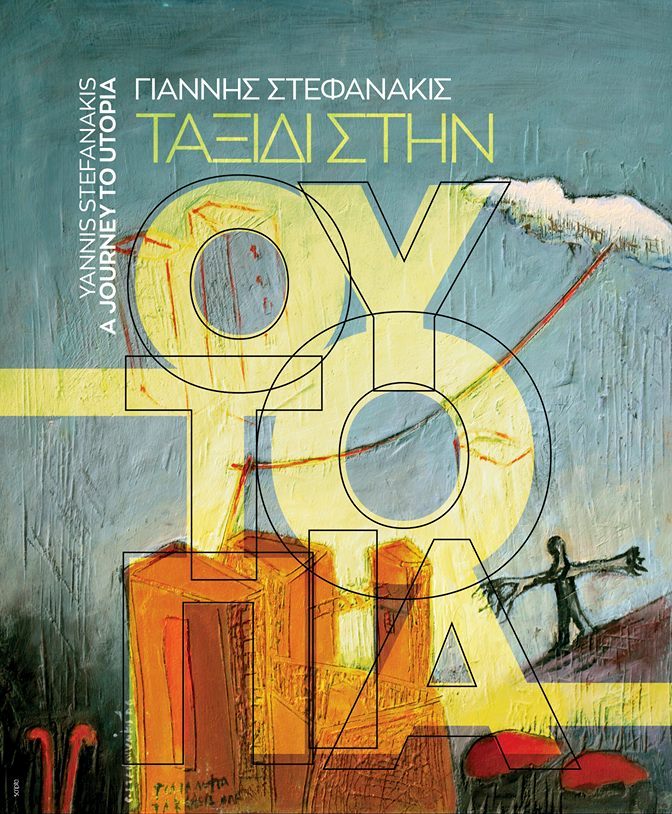

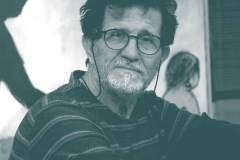

Engraver and painter, poet and teacher, video-artist, printer of collector’s editions and cultural magazines, Yannis Stefanakis chooses to produce art using various means of expression on the example of the Renaissance Man and, in his work as a whole, to draw contemporaneity into History, art into life, utopia into reality, modern technology into individual creation. Contemplative, consistent and persistent, socially aware, he dispenses his life among images, words and multiple forms of artistic pursuits, always calling for communication, not in its commonplace, timeworn sense, but in the sense of interaction on the level of memory and knowledge, of blending the old with the modern, of contrasting illusion with truth.

He lived an adventurous life, with constant inland migrations, which somehow defined himself and his art. He was born in the village of Grigoria in Heraklion, in the area of Messara. He would make his toys himself, using such materials as big pumpkins, nails and wood – a real party for Yannis and his brothers. He was only twelve years old when he went to Heraklion to become a carpenter. He soon learned how to work wood, perceive its vertical and horizontal grain, its soughs and irregularities, discovered carving and engraving methods, and the ways to transform it and make utensils out of it. Then another relocation followed. A year later, a first cousin of his was meeting him in Piraeus – he would work with him in an underground printing shop in the centre of Athens. The amateur engraver discovered xylography and combined it with printing. It opened up a whole new world for him. His encounter with the libertarian poet Michalis Katsaros in 1978 – always within the framework of his search for new spiritual values and means of expression – resulted in the publication of the short-lived poetry journal Epipedo. He later published the Neo Epipedo, an artistic production of his own. Released to date with the help of his wife, the painter Margarita Vasilakou, the journal deals with contemporary literature and poetry, and explores the discourse and theory in visual art.

His ambition and need for extensive knowledge led him to the Athens School of Fine Arts, where he studied painting, engraving, religious painting, printing and book art. Specialized knowledge influenced his techniques and expanded his horizons. He gradually became a multitasking manual worker, enthusiastic about several different means of expression, constantly coming up with new methods or techniques, and not the least insensitive to the technological advances of the time. Whatever his artistic result was, whether in painting, engraving or video-animation, it was the product of hard work, sensitivity and imagination, of poetry merging into reality moments, an artwork infused with the experience of a solitary man-creator on the tormented path of his life and art.

Analyzing Stefanakis’ work in general to date brings about the realization that, to a greater extent, he acts as the narrator of short, fragmentary, poetic stories. Only he recounts them indirectly, through lines, colours, squares and rectangles, small sculptures. His visual art vocabulary consists of a palimpsest of concepts and techniques.

The fantastic element unfolding throughout his work directly relates to the irrational and clearly points to the dichotomy of reality with which he also seems to be mostly preoccupied. He seems to be seeking the boundaries between real life and spirituality, knowledge as opposed to the bulk information overwhelming our daily life and surrounding, the course of human existence in a world filled with absurdity. Moreover, he seems to the looking for those rifts that enable Man to reverse Sisyphus’ vain, futile and solitary course, and turn it into a worthwhile collective path.

Printmaking: experiments with drawings and colours

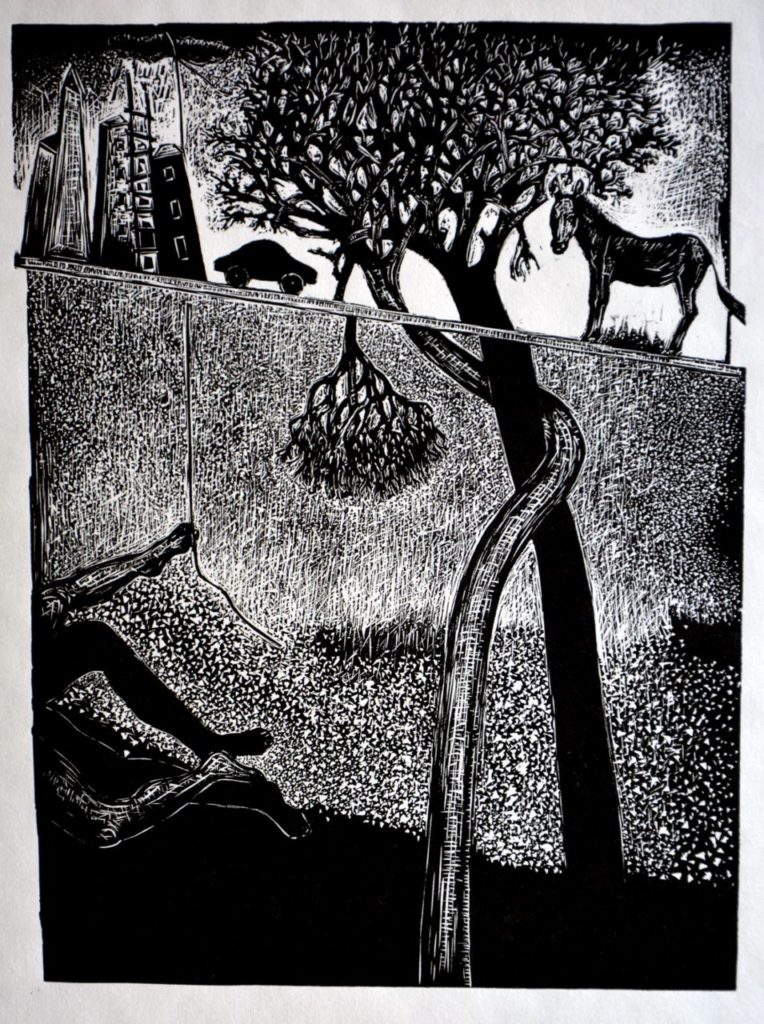

Besides his first – to some extent – traditional sketchings, Yannis Stefanakis’ printmaking gradually develops into an anti-academic art, original in composition, without thematic constraints, but with much artistic experimentation. And these experiments are mainly with colour beyond the limits of black and white, as prevailing in the engravings, and spread out boldly in blues and reds. The artist’s poetic look chooses memory or everyday images, and transposes them onto his material. Buildings, nocturnal sceneries, neoclassical façades, indoor spiral staircases, landscapes and windows, whorls, images from the Stone Age. All are recast into woodcuts, lithographs, mixed media artworks. He masterfully pours ink, either black or colour. Thickening it here, diluting it there. He creates shades, blends colours. He is not afraid of the white, uses it where needed, often likes to encircle it with black – a square within a square. Sometimes the embedded square breaks the limits of the frame and, through a different writing, selectively spreads out to the parts of a larger form.

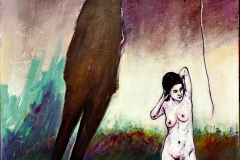

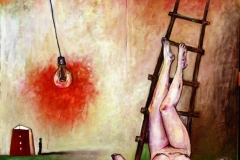

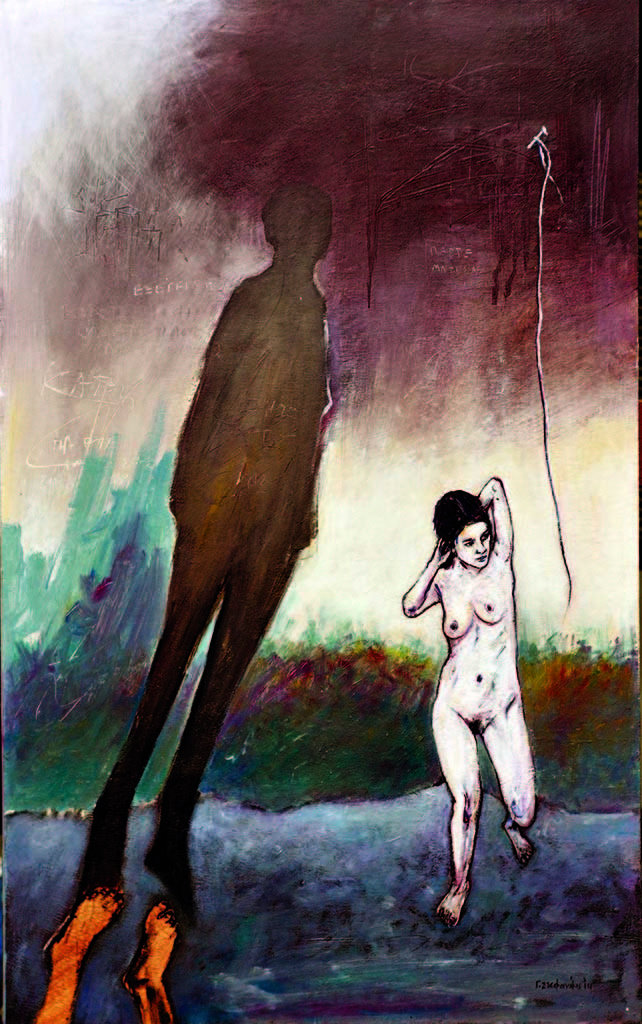

He uses expressionist, surrealist and abstract elements, easily handles the contrasts of volumes, the geometric perception of things, and infuses the concomitant engravings with intensity, manipulating the game of light and shadows to give volume to the architectural images or objects integrated in his compositions. Many of his creations discuss the inner meaning of human existence, his main hero’s loneliness, whether man or woman, the adventure in gender relations, the image of modern cities as appealing architecturally, but also as contributing to human isolation, the concept of utopia through a transcendental path to the sky or a stairway leading to heaven, to the world beyond, as it were. For the artist, the metaphysical dimension of his printmaking and painting may constitute another of his quests beyond the breakable boundaries of everyday life.

If one considers the whole of his printmaking work so far, one realizes that the entire history of Man’s art appears to be there. From prehistoric, to modern and contemporary art. Its rich thematic content, comprehensive in meanings and simple in actualization, demonstrates that the engraver has already shaped his own personal idiom and acts as a distinct monad in his art community. Probably among the most interesting visual elements emerging in his engraving, the ark, the window and occasionally Man represent topics that evolve with a different, perhaps more conceptual, orientation in Stefanakis’ work.

Painting: game with concepts and materials

Let us take Yannis Stefanakis’ first exhibition entitled Mia afirimeni oikologia [An abstract ecology] as the threshold of his painting career. His themes deal with the evolution of life, nature, its alleged upcoming extinction. The 1980s see the beginning of a period of economic prosperity and the emergence of environmental movements consciously expressing concerns about the future of the planet. Among other things, the artist uses trivial everyday materials such as stones, wood, lime and sand in order to create the rugged texture of his painting surfaces, where matter and colour coexist and define each other. Although abstraction dominates on the first level, fish fossils, burnt trees and burning areas can be dimly distinguished on the second level. Techniques are balanced optimally; the artist creates a tense and misty atmosphere. He does not only reproduce his metaphysical anxieties most forcefully, but also the (symbolic and real) threatening cloud of the surrounding area.

The Window of the Picture later depicts the artist-poet’s introspective mood. A daily human movement is transformed into a comprehensive painting performance. The ordinary opening of the window from the inside-out is reversed, being carried out from the outside-in. The space within is plain and symbolic. Selected inner images and encased memories are converted into minimal messages to the outside world, where image and speech chaos prevails. Its big frames look like boxes where, as through a window, the artist’s demands are formulated: art is a matter of priority; it is a matter of ethics and customs, of historical memory and life choices.

A few years later, the windows of his previous artwork become a subsequent composition consisting of three-dimensional cubes. It is symbolically entitled Kyvotos [Ark], with all that the word entails in signs and interpretations. In the small boxes, he places fragments of memory: a bird nest, a prehistoric whorl, hydraulic tools, solitary human figures, parts of a loom, bread as the essential food commodity of life. Using his own simple means, he narrates fragmentary stories, makes allusions to values unique to him. He indulges in a game between painting and assemblage, while maintaining perfect balance. Besides the purely aesthetic elements featuring in Stefanakis’ work, poetry is also characteristic of it. Poetry is indeed noticeable to some extent in the whole of his work, but it dominates this specific artwork.

His next artwork, Technopaignion, represents the painter’s real game with time and with the viewer. The artist returns to his mischievous school years and visually reproduces the lived time of childhood. School pictures, the boys’ traditional whirligig, the bloody knee, the migratory swallows, the legendary paper airplane, the hopscotch on the street, the chalk, the kite are only a few of the Technopaignion’s symbols. In this game, the viewer is incited to in turn contemplate and reflect on the years of lost innocence. Quasi-photorealistic painting, engraving, assemblage, collage, multiple printing, graffiti and writing coexist and, to a great extent, reshape what is long gone. Stefanakis implicitly keeps track of that time which eradicates everything, leaving only faint memories behind. The past, the present and occasionally the future mark many of his work, as references to memory, to selective secularity, to authenticity.

From 2003 onwards, the cities play a leading role in the artist’s painting, as in Eikones periplanisis [Images of Wandering], Omorfes poleis [Beautiful Cities] i.a. At first glance, the viewer’s interest focuses on the architectural buildings themselves. Rectangular boxes with windows, nondescript and without any signs of life, isolated stairways extending to touch the sky, boxes placed next to each other recall the Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. The crisis of the big city is the other side of the crisis of nature. The enclosed spaces of the cities suggest the confinement of people and feelings. A lonely man wanders among them. He seems to be looking for escape routes out of a city that is at once so familiar and so unsuitable to him.

The Window of the Picture later depicts the artist-poet’s introspective mood. A daily human movement is transformed into a comprehensive painting performance. The ordinary opening of the window from the inside-out is reversed, being carried out from the outside-in. The space within is plain and symbolic. Selected inner images and encased memories are converted into minimal messages to the outside world, where image and speech chaos prevails. Its big frames look like boxes where, as through a window, the artist’s demands are formulated: art is a matter of priority; it is a matter of ethics and customs, of historical memory and life choices.

A few years later, the windows of his previous artwork become a subsequent composition consisting of three-dimensional cubes. It is symbolically entitled Kyvotos [Ark], with all that the word entails in signs and interpretations. In the small boxes, he places fragments of memory: a bird nest, a prehistoric whorl, hydraulic tools, solitary human figures, parts of a loom, bread as the essential food commodity of life. Using his own simple means, he narrates fragmentary stories, makes allusions to values unique to him. He indulges in a game between painting and assemblage, while maintaining perfect balance. Besides the purely aesthetic elements featuring in Stefanakis’ work, poetry is also characteristic of it. Poetry is indeed noticeable to some extent in the whole of his work, but it dominates this specific artwork.

His next artwork, Technopaignion, represents the painter’s real game with time and with the viewer. The artist returns to his mischievous school years and visually reproduces the lived time of childhood. School pictures, the boys’ traditional whirligig, the bloody knee, the migratory swallows, the legendary paper airplane, the hopscotch on the street, the chalk, the kite are only a few of the Technopaignion’s symbols. In this game, the viewer is incited to in turn contemplate and reflect on the years of lost innocence. Quasi-photorealistic painting, engraving, assemblage, collage, multiple printing, graffiti and writing coexist and, to a great extent, reshape what is long gone. Stefanakis implicitly keeps track of that time which eradicates everything, leaving only faint memories behind. The past, the present and occasionally the future mark many of his work, as references to memory, to selective secularity, to authenticity.

From 2003 onwards, the cities play a leading role in the artist’s painting, as in Eikones periplanisis [Images of Wandering], Omorfes poleis [Beautiful Cities] i.a. At first glance, the viewer’s interest focuses on the architectural buildings themselves. Rectangular boxes with windows, nondescript and without any signs of life, isolated stairways extending to touch the sky, boxes placed next to each other recall the Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. The crisis of the big city is the other side of the crisis of nature. The enclosed spaces of the cities suggest the confinement of people and feelings. A lonely man wanders among them. He seems to be looking for escape routes out of a city that is at once so familiar and so unsuitable to him.

If the notion of the ark recalls the myth of Noah and his attempt to save himself, his family and every living being after the deluge, from his perspective the artist seems, in turn, to want to preserve fragments of the humanist culture of the previous centuries for the generations to come. In difficult times such as the entire 20th century and the first decades of the 21st century that loom ahead, the artist endeavours to enclose both primeval and timeless values and concepts as intended for Man’s future spiritual survival. And this indeed constitutes one of the most interesting elements of his work on the level of communication: not only does he dialogue with the viewer through the image, but he goes further by daring them to reflect on it, on its conceptual meaning which is not always fully related to the topic or form, but goes deeper into analytical and synthetic frames of thinking.

Since 2012, at variance with painting, engraving and assemblage, Yannis Stefanakis has been producing short video-animations (animated cartoons), training himself and his viewers artwise to a newer, more massive and mainly more familiar form of expression. He does not distance himself from his painting though, since he rests on it to produce short, self-contained films. In most of them, the leading role is held by male or female nude characters, key figures from his paintings or engravings, forms that acquire motion accompanied by sounds. Counted among the most characteristic ones, Akropatontas (2012) [Tiptoeing], a black and white film of exceptional quality about the relations between men and women. In the Images of Wandering, the fictional hero wanders around in the artist’s well-known landscape paintings, appropriates his artistic symbols and uses them at will. In the optimistic Ptosi [Fall] – Short Film Festival in Drama (2017) –, the same hero attempts an abrupt descent from the terrace of an oblong apartment block and, on his way down, notices the artworks or images that have marked him, through the open windows. After setting foot on the ground, he twitches, leaves everything behind and moves forward toward the future… In Antimetopous (2017) [Confronted], Stefanakis again deals with the gender relations of attraction and repulsion (fear). In Stigmi (2018) [Moment], perhaps his longest film that also took part in last year’s Short Film Festival in Drama, the hero is not the artist’s male alter ego figure anymore, but the artist himself holding a white canvas frame while on his way to the unknown, who moves around among his own landscape paintings, chooses his own symbols and creates one more artwork. Which is nothing other than an image of condensed thoughts, concerns, hopes, creative anguish, sensitivity and poetry.

Peggy Kounenaki

Art Critic, Journalist, Writer

(November 2018, Chania)